The general character of sherry wine, its own identity, is not merely the result of a geographic origin, no matter how exceptional the natural conditions which converge within the Jerez Region. For over 3,000 years different historical circumstances have moulded the identity of these wines, in the same way that the wine itself, its production, sale and enjoyment have supposed a determining factor in the history of the region and the cultural identity of its inhabitants. Sherry wines are the result of mark left upon this land by very different cultures, some very distant in origin. Different civilizations which over the long years, seduced by the land, have each made their contribution to a product which is, above all, cultural. A certain knowledge of history is fundamental if we are to fully understand the genuine personality of sherry wines. The history of the Jerez Region is the history of its wines.

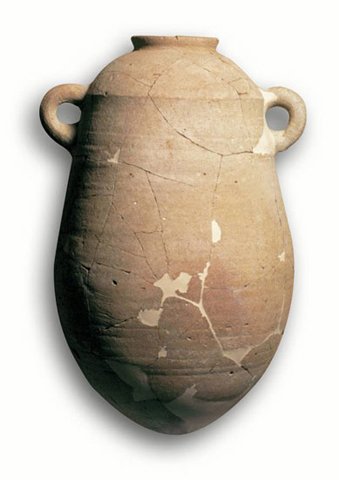

The very first mention of Sherry wine comes from the Greek geographer Strabo in the 1st Century BC. In his book Geography (volume III) he writes that the first vines were brought to the Jerez Region by the Phoenicians in 1100 BC.Archaeological sites of Phoenician origin have been discovered in excavations at Castillo de Doña Blanca, located just 4km from Jerez, where the remains of wine-presses have been found. This discovery confirms that the same people who founded the ancient town of Gades, or Cádiz, brought with them the art of cultivating the vine and wine making from the far off lands of what is now known as Lebanon.

From Xera, the name given by the Phoenicians to the region where Jerez stands today, this nation of traders produced wines which were then exported throughout the whole Mediterranean Basin, especially to Rome. Thus, right from its most remote origins, sherry wine acquired one of its most important characteristics, one which has become an identifying factor over the centuries: that of being a wine which "travels".

Greeks and Carthaginians also had an important role to play in the history of the region, rooted deeply in the Mediterranean culture of wine and moderation.

Around the year 138 BC the Betica Region was pacified by Scipio Aemillianus, who established Roman rule and opened up a substantial flow of trade between the region and the metropolis. The people of Cádiz, the Gaditanos, exported local products to Rome: olive oil, wine from the Ceret region and garum (a kind of marinade sauce made from leftovers of salted fish). By this time the fame of "Vinum Ceretensis" had already crossed over our frontiers and was not only highly appreciated in Rome but also in many other parts of the Empire, a fact proven by the discovery of numerous archaeological remains in the shape of amphorae which, for tax purposes, bore a stamp on their clay surface which stated their content.

The Roman writer from Cádiz, Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (born during the first years of the Christian era), in his De re rustica, in which he lays down basic rules for vineyards in the Jerez area which have survived to the present day: soil and grape types, vineyard location, various vineyard tasks and at what time of year to carry them out, the quality of must obtained, and so on.

The year 711 AD marked the commencement of Moorish denomination in Spain, opening a period of history which in the case of Jerez would last for over five centuries. During all this time Jerez remained a large wine producing centre, even though the Koran prohibited the consumption of alcohol.

To a certain extent the production of raisins, the distillation of alcohol for a variety of different uses (perfumes, ointment, etc...) and the use of wine for medicinal purposes provided the pretext to continue growing vines and making wine. In fact, in 966 the Caliph Al-Haken II decreed the grubbing up of the Jerez vines on religious grounds, only to be informed by the people of Jerez that the grapes from their vineyards were used to produce raisins to feed the troops fighting in the Holy War, which was indeed partially true, and thus ensured that only a third of their vineyards were grubbed up.

In any case we know that during specific periods of reduced religious fervour wine was both widely appreciated and consumed, especially in the more elite social circles of the time.

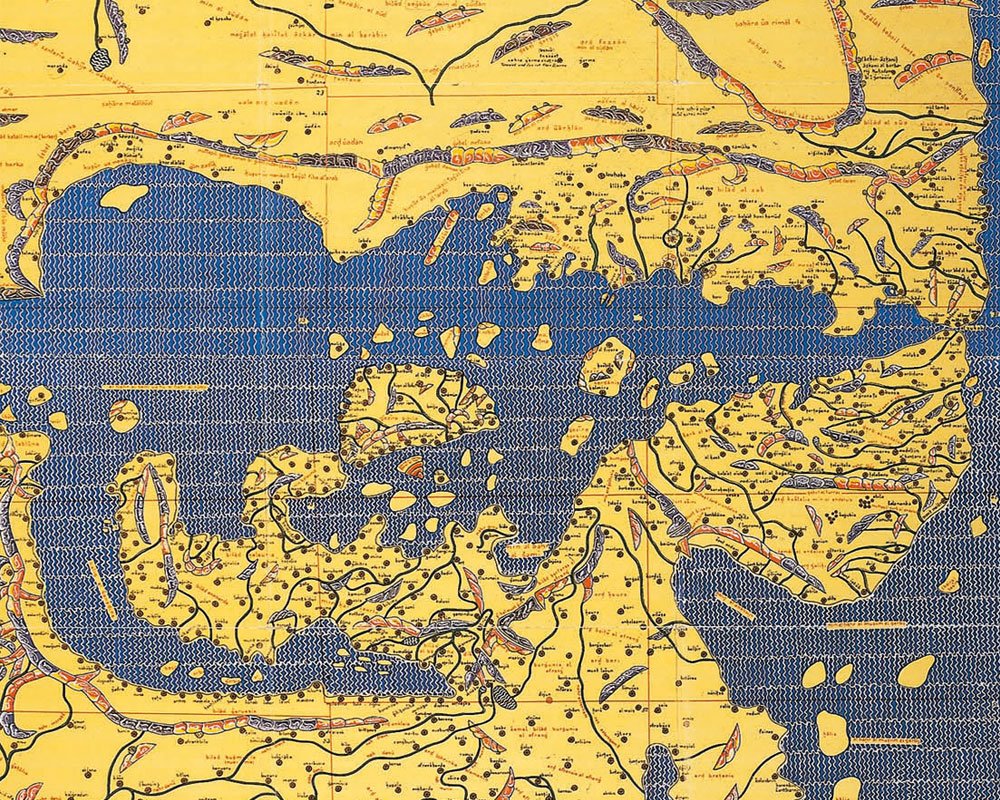

A map of the region dating from 1150, designed by the Moorish geographer Al-Idrisi and commissioned by King Roger of Sicily is kept in Oxford University's Bodleian Library. A curious feature of the map is that the North is at the foot of the page and the South at the top. The map clearly shows the name given to the city by the Moors, which is no other than Sherish.

In 1264, King Alfonso X of Castile reclaimed Jerez from the Moors, and life in the Sherry region changed radically.

Located at the frontier with the Nasrid kingdom of Granada - hence its full name, Jerez de la Frontera - the city underwent years of bitter struggle, violence and bloodshed, during which replenishment of both population and crops became essential.

A reward system associated with the Conquest had been created, with the Crown distributing specific units of land on the basis of social prestige and merit. Vines and cereals, obligatory crops by law, became the economic and dietary lynchpins of a territory of which Alfonso was very fond and where he owned his own vineyard.

Tradition has it that one of his most important military officers, Fernán Ibáñez Palomino, gave his name - Palomino - to the variety of grape that later became a local classic.

Around this time, and even in the 12th Century, sherry wines were being exported to England, where they were known by the Moorish name for the city: Sherish. However, our wines became popular in this country when Henry I proposed a bartering agreement to promote national produce: English wool for sherry wine. The Jerez vineyards then became an important source of wealth for the kingdom, so much so that King Enrique III of Castile prohibited the uprooting of even a single vine by Royal Decree in 1402. Even going as far as to forbid the placement of bee-hives in close proximity to the vineyards in case the bees should damage the grapes.

The growing demand for sherry wines from English, French and Flemish merchants led the town council to establish the Regulations of the Guild of Raisin and Grape Harvesters of Jerez on 12th August, 1483. These were the first rules governing our Denomination of Origin: regulating all the details of the harvest, the characteristics of the butts, the ageing system and commercial procedures.

Overseas sales of Sherry Wines underwent a further period of expansion after the wedding of Catherine of Aragon, youngest child of the Catholic Monarchs, first to King Arthur of England, and later to King Henry VIII. Catherine, an educated woman, voiced the complaint that "The King, my husband, keeps the very best wines from the Canaries and Jerez for himself".

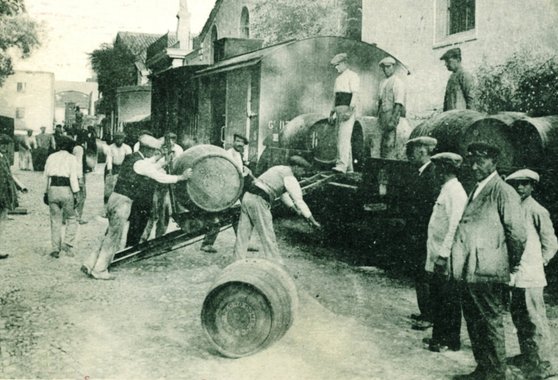

But Sherry Wine was not just exported to Europe. The discovery of America was to open up new markets and business flourished as a result. This was the period of epic voyages and geographical discovery. A series of historic events were celebrated with Sherry wine, as proven by the fact that Magellan purchased 417 wineskins and 253 kegs of Sherry before setting out on his long voyage, which means that Sherry was the first wine to complete a voyage around the world (that is if any remained by the time the Nao Victoria returned to Sanlucar under the command of Juan Sebastian Elcano).

There is also evidence that Sherry wine was present at events celebrating the conquest of new territories such as Venezuela and Peru.

Exploitation of this 'immense New World' was effected by the Spanish Crown through the port of Seville and the commercial exchange known as the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), also in Seville, the sole government agency authorised to control Spanish exploration and colonisation of the new lands. This circumstance was extremely favourable for sherry wines as, being so close to Seville, they formed an essential part of the provisions for all those vessels sailing to America.

The wine-growers of the Jerez region took advantage of a provision which stipulated that a third of the cargo space in each ship on each vessel trading with America be reserved for goods from the Cádiz area. This was especially beneficial as from 1680 when the head of the fleet moved to Cádiz, thus bringing to an end the monopoly over all trade with the Indies held until that time by the Port of Seville.

This trade with the Indies transformed small family wine businesses into truly large, industrial operations. Numerous Italian investors and traders, such as Lila, Maldonado, Spínola, Conti, Colarte, Bozzano and Zarzana settled in Jerez during the 15th Century.

The sale of Sherry in the Indies was frequently hampered by pirates who seized the fleet's cargo and sold it in London. The greatest haul of sherry wine was made in 1587 when Sir Francis Drake attacked Cádiz and carried off 3,000 kegs of sherry. When this booty arrived in London it made sherry fashionable in the English Court and Elizabeth I even went as far as to recommend it to the Count of Essex as the best of wines. As a consequence of this rapid increase in the consumption of sherry and a limited supply, King James I decided to set an example to his subjects by ordering that the Royal Cellars should limit the amount of sherry brought to his table to a modest 12 gallons (48 litres) per day!

The works of William Shakespeare give us a good idea of the popularity of sherry wines in those days. Together with his friend Ben Johnson he used to drink a good few bottles of sherry each day at the Bear Head Tavern. The Bard frequently refers to sherry in many of his plays: Richard III, Henry VI, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Henry IV, etc... In his Palinodia (1619), Pasquil declares that "all drinks stand hat-in-hand in the presence of sherry."

During this period, British merchants purchased most of the Sherry produced, but they didn't make any significant investments in the area, with some exceptions, such as Patrick Murphy.

The first entrepreneurs who invested in the creation of substantial soleras of matured wines and the construction of large bodegas for their production were Spanish, including Antonio Cabeza de Aranda (the CZ brand), Carlos Bahamonde, José López Martínez; Spanish citizens of French descent, such as Juan Haurie, Juan-Pedro Lacoste, Pedro Beigbeder; and, a few of them, British merchants, such as James Duff (in partnership with Juan Haurie) and Arturo Gordon

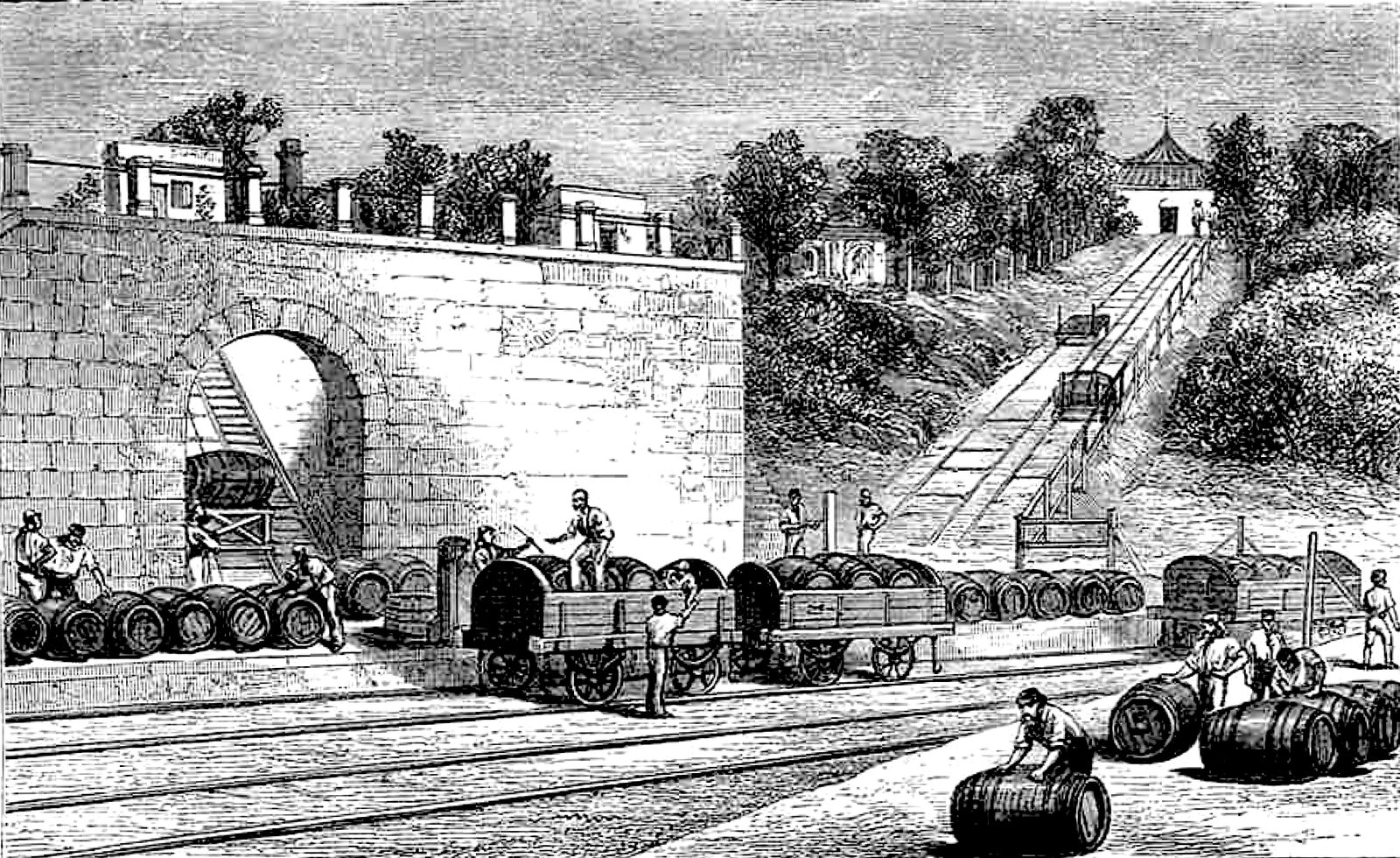

After the war against England and the Spanish War of Independence, the wine industry in Jerez grew significantly thanks to new investments from the indianos (colonists in America) who returned to Spain due to the independence of the American colonies (Benigno Barbadillo, Vicente-María de la Portilla, Antonio Ruiz Tagle...), from British merchants established in or recently arrived to the area (J.W. Burdon, Wisdom & Warter, Mackenzie, Williams & Humbert, Sandeman...), and from Spanish entrepreneurs: Juan Sánchez (founder of Sánchez Romate), León de Argüeso, José-Antonio Sierra, Cayetano Ñudi (Delgado Zuleta), Antonio Fernández de Valdespino, Eduardo Hidalgo, Manuel-María González Ángel (who later partnered with R.B. Byass), Manuel Misa, Carlos Otaolaurruchi...It must be noted that an important part of the capital invested in the Sherry industry by British entrepreneurs was acquired by them in the first place through their activities in the area, so it can't be considered foreign capital. Such is the case of, among others, Patricio Garvey and Tomás Osborne Mann, who respectively generated their capital as industrial partner to several bodegas and as merchant and banker.Moreover, some companies based in England and France had Spanish partners as main shareholders, such as E. Ostmann and Julián Pemartín y Cª, whose majority partners were the Marquis of Villavelviertra and Fermín Apecechea, respectively..These investments, together with the prestige of Sherry wines, caused an increase in international sales, which in the 1840s represented 20% of the total value of Spanish exports.

However, this 19th century boom could not have happened in the absence of a certain set of conditions, which will be analyzed in the next chapter.

In the mid-eighteenth century the wines being exported from the Jerez Region to overseas markets were very different to what we now recognise as Sherry Wine.

Demand for wines of all types grew from the end of the seventeenth century onwards, mainly in the countries of northern Europe, and particularly in Great Britain and Holland - the great maritime powers of the period - and the different wine producing regions had begun to adapt their production systems to meet this demand. British taste began to change: hitherto predominantly inclined towards light, pale wines, it now began to show a preference for stronger ones with more colour and maturity.

In Jerez this transformation of the market caused understandable differences between the vineyard owners and local merchants, which were not easy to overcome. The former wished to find a market for their current year must and clarified wines, which required fortification to prevent them spoiling during long voyages. Naturally, the latter were more interested in meeting market requirements and were demanding different types of wines.

The trade associations of the time, which dominated the local wine industry, were strongly protective of the privileges of local vine-growers and proved to be a restrictive element as far as trade was concerned. The profuse and complex norms of the Vintners' Guild restricted the possibility of ageing wine, considering this to be a speculative practice, thus favouring the trading of young wines whilst at the same time hindering the producers, or "extractors", from selling the type of wine for which demand was steadily increasing.

1775 was the year which marked the commencement of the so-called "Extractors' Action", a law-suit instigated by local producers including numerous foreign traders who had settled in the region. This process concluded several decades later with the abolition of the Vintners' Guild. During this period the Guild's restrictive code of practice gradually disappeared, which in turn generated a movement towards liberalisation and a strong momentum for wine production and trade.

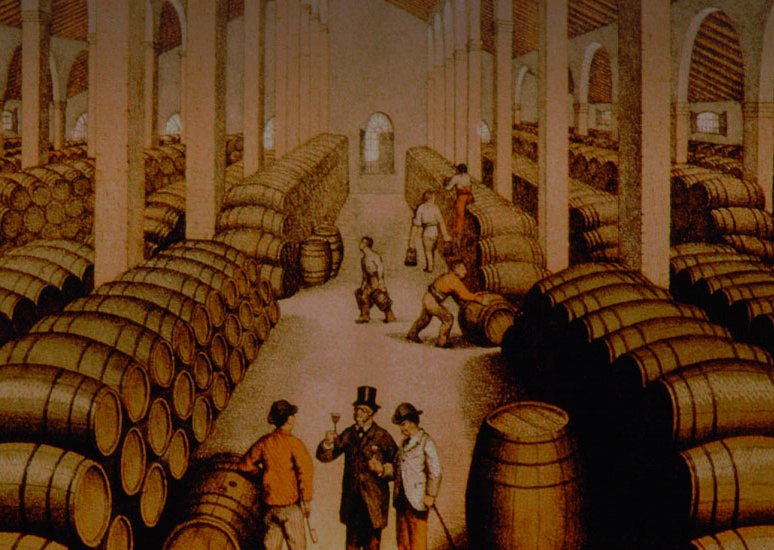

More importantly, this process also helped shape the identity of the Region's wines. The prolonged storage of wines from different harvests together with the need to supply the market with a product which was consistent in quality gave rise to one of the major characteristics of sherry production: the ageing method known as Criaderas and Solera.

Moreover, as the wine was now left to repose for much longer in the casks then the concept of fortification, previously used to stabilise more delicate wines, suddenly changed to become a true oenological technique enabling the wine-maker to decide the type of wines he wished to produce; the addition of grape distillate in different proportions providing the origins of the wide range of sherry wines available today.

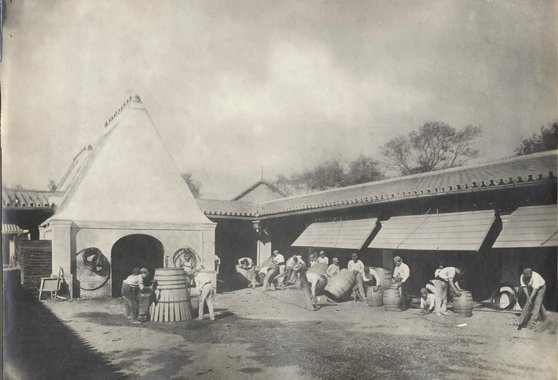

This was also the age of the great ageing bodegas. In an attempt to provide optimal architectural conditions for ageing wine whilst embracing the neo-classical aesthetic that was then so fashionable, Gordon, Lacoste, Haurie and other exporters created the great sherry houses that are so impressive even today.

The leading figures behind these changes were in many instances long established foreign merchants already settled in the region, such as Juan Haurie, Oneale, Lacoste, Juan Domecq, Patricio Murphy, etc..., but local growers were also involved in the ageing and trading phases of the business (Cabeza, Menchaca, Rivero, López Martínez, etc.).

Towards the end of the 19th Century, as occurred in almost all European vineyards, the black plague of phylloxera devastated the vineyards of the Jerez Region. An insect imported from America (Daktulosphaira vitifolii) provided the worst blow suffered in the history of wine-growing, destroying the Jerez vines and blocking their roots. The first outbreak had been detected several years earlier on numerous vineyards in other parts of Europe, thus by the time the insect spread to the Jerez Region the only solution to a problem of such magnitude was well known by all: uproot all the vines and replant with American rootstock varieties, resistant to the insect, upon which local varieties of vine were then grafted.

Recuperation of the vineyards was a relatively rapid process when compared to other regions in Europe and brought with it the definitive selection of the grape varieties which are still used to make sherry wines today.

The following years were prosperous ones and in the early decades of the 20th Century improvements in communications and transport allowed sherry wine to expand into international markets. It was during this period, however, that a new problem reared its head, one which had been latent for years but unnoticed by the sherry firms of Jerez: the usurping of the identity of Sherry Wine.

The British were unquestionably responsible for the increased popularity of Sherry throughout the world and not only did they pass on their enthusiasm for the beverage to their numerous colonies around the globe, but in those where it proved possible to produce wine they began to make drinks of certain style which were reminiscent of authentic sherry from Jerez, giving them names such as "Australian Sherry", "South African Sherry" and "Canadian Sherry". The problem of imitations had arisen, and one which unfortunately remains.

These are the years during which legislation begins to recognise such concepts as the protection of intellectual property and propose defence mechanisms against usurpation and imitation. A concept of enormous importance arose in this context: the Denomination of Origin. This was a concept which first appeared in the context of wine production and has since been applied to other food products.

In the latter half of the 19th Century the wine producers of the Jerez Region, true businessmen who were in many ways ahead of their time, had attended a series of international conferences which established the legal framework for the defence of Denominations of Origin.

It is not unusual, therefore, that when the first Spanish Wine Law was published in 1933 it made reference to existence of the Denomination of Origin Jerez and its Consejo Regulador, the first to be legally constituted in Spain.