Ageing is without a doubt the decisive stage in the Sherry production process: the most prolonged in terms of its duration and a stage which witnesses the appearance of organoleptic characteristics which give rise to a whole range of different types of Sherry wines.

Two types of crianza are carried out in the Jerez region: one that consists of storing and developing wine in wooden butts, where it undergoes slow, physico-chemical development influenced by surrounding conditions, known as envejecimiento (maturing) or oxidative ageing; and another known as biological ageing, a process that takes place under a film of yeasts known as velo de flor, during which the wine develops in a more dynamic way, driven by what goes on within the biological layer formed on its surface by specific indigenous ambient yeasts.

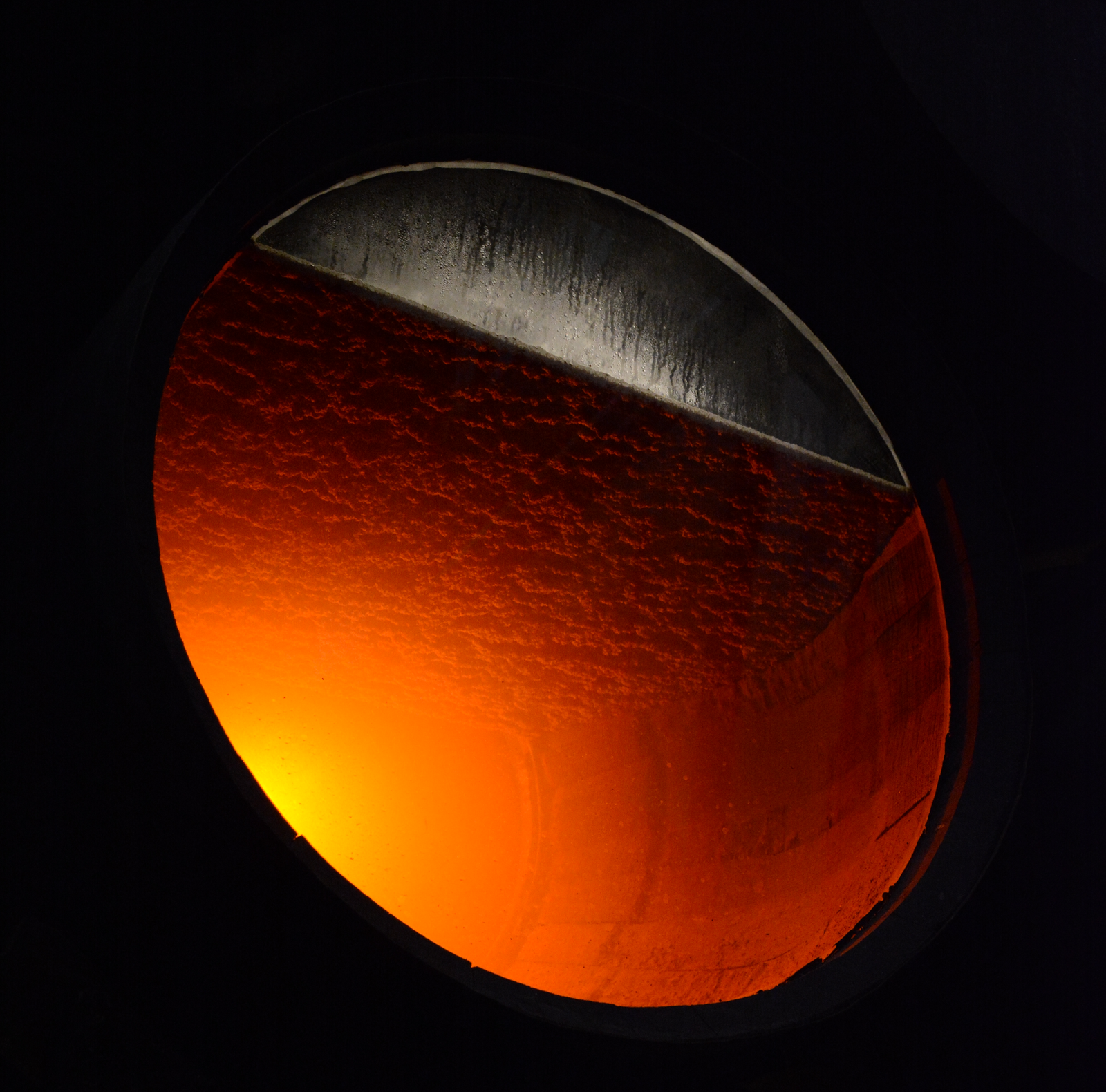

In the case of biological ageing the influence of the flor is decisive: not only does it protect the wine from oxidation by preventing direct contact between the liquid and the air contained within the butt, but also the interaction of the yeast and the liquid brings about significant changes in the same: to the already mentioned consumption of alcohol as a consequence of its being metabolised by part of the flor must be added the consumption and consequent reduction of another series of elements initially present in the wine, such as glycerine or volatile acidity. Biological ageing, on the other hand, brings about a substantial increase in the content of acetaldehydes which are responsible for the sharp sensation in the nose which wines aged by this process gradually acquire.

Oxidative ageing, however, facilitates the appearance of radically different characteristics in the wine: with a greater degree of alcoholic strength and in direct contact with oxygen in the air, the wine becomes gradually darker and is more clearly affected by the phenomenon of concentration produced as a consequence of the transpiration of specific elements in the wine through the walls of the butt.

“Ageing is without a doubt the most decisive stage in the Sherry production process.”

In accordance with the Pliego de Condiciones the ageing of sherry wines must be prolonged for a minimum period of two years. Frequently, the ageing time is much longer so that the wines may develop the distinctive characteristics of each type.

Although in the case of oxidative ageing it is in fact possible to carry out static ageing without blending wines of differing ages, the traditional system in the region (and the only viable method with which to successfully carry out biological ageing) is the dynamic ageing system known as "criaderas y soleras".

The nature and capacity of the containers used in sherry-making have evolved over the course of its long history. The earliest vessels were earthenware amphorae and jars, and these continued to be used for over two thousand years. From the Middle Ages on, when the significant advantages of using wooden casks for transporting sherry became apparent, these also came to be used as storage or ageing containers. Changing the nature of the receptacle was to prove a milestone in the career of the region's wines in that it was instrumental in effecting major changes in their composition and sensory properties, effectively creating the prototype of the sherry we know today.

The wooden casks used for ageing have varied widely in size, capacity and type depending on winery conditions and storage space. Toneles, toneletes, bocoyes, botas gordas, botas largas, botas cortas, medias botas, cuarterones and barriles, ranging in capacity from the 900 litre tonel to the 16.66 litre one-arroba barril, have all been used for ageing wine and their presence has configured winery spaces. Various woods - chestnut, local oak, American oak, and so on - have likewise been used.

Nowadays, although casks of various types are still in use in many bodegas, the preferred and most widely employed type is the American oak 600 litre (equivalent to 36 arroba) butt, also known as a bodega butt. This type of wood is preferred to any other because of the specific contribution it makes to sherry, and it is furthermore traditional: it has been used since the first trading exchanges with the Americas, from which Spain imported wood and to which it exported wine.

The butts are not usually filled to the top: in the case of butts used for ageing wine under flor they are filled up to 30 arrobas (500 litres), leaving a space equivalent to that of "two fists" of air. This permits the creation of a surface area upon which the flor may develop and provides a sufficient surface/volume ratio for the influence of this upon the wine to be ideal.

The wooden butt is neither a completely air-tight nor an inert receptacle since the wood is permeable to oxygen and also absorbs water from the wine it contains and then releases it into the winery's atmosphere. This transpiration causes the volume of wine in the butt to drop, the rate of loss increasing the drier the winery atmosphere becomes. This evaporation effect is known as merma and accounts for losses of 3 percent to 5 percent per year of the total wine stored. However, as the loss is essentially accounted for by water in the wine, this means that its other components are continually being concentrated.

After long years of crianza, this is discernible in the increased alcoholic strength of wines aged without the protection afforded by a film of flor. This concentrating effect is not the only modification that will take place in the wine: it will also be enriched by subtle, specific contributions from the wood of the butt, which will have been thoroughly wine-seasoned before being put into service as an ageing receptacle. Meanwhile, the wine will have been developing gradually in this special environment by virtue either of the gradual but continuous impetus provided by the dose of oxygen that the wood allows to penetrate into its interior, or, in a different - more dynamic and substantial - way, of biological ageing beneath a film of flor.

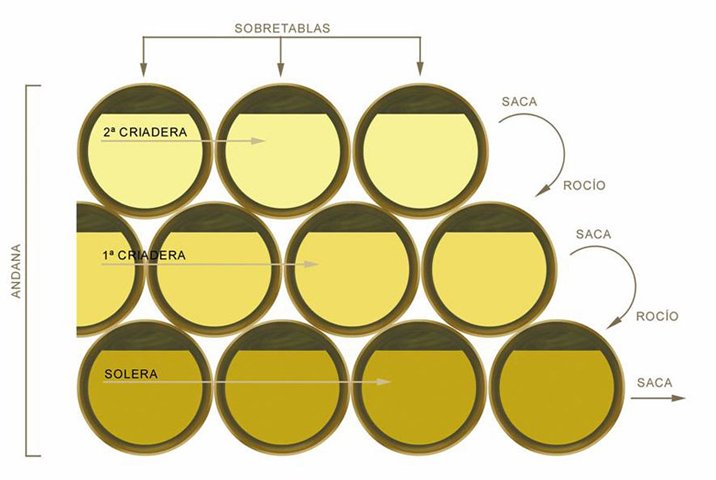

The traditional, genuine system used for ageing sherry wines is known as the Criaderas and Solera System. This is a dynamic system by which wines from different stages of the ageing process are blended together in order to perpetuate specific characteristics in the wine which is finally sold on the market, which is a result of combining all the different vintages.

The successful development of this ageing method requires a very precise arrangement of the sherry casks in the bodega according to the different levels of age, a process which takes place in what is known as the criaderas. Each solera is made up of various 'scales' or tiers, each in turn composed of a particular number of butts. The tier that contains the oldest wine is at floor level (the term 'solera' derives from the Spanish word for floor - suelo). The tiers placed on top of this, containing progressively younger wine the further away from the floor they are, are called criaderas (nurseries) and numbered according to their closeness in age to the solera tier (the closest being the 1st criadera; the next one, the 2nd criadera, and so on).

The solera, or tier pertaining to the oldest level of the ageing process, produces sherry ready for bottling. Periodically, a specific proportion of the wine in each of the butts making up the solera system is extracted, leaving them partially empty. This operation is known as saca (taking out). The space thus created in the solera (floor-level) casks is topped up with wine taken from the next oldest scale, namely the saca from the 1st criader which sits in the tier above. The space thus created in the 1st criadera is then in turn topped up with wine similarly removed from the 2nd criadera, and so on up to the youngest scale, which is then topped up with wine obtained from the añada system. The operation of topping up, or refreshing, the space created in a scale is known as rocío (sprinkling), and the whole process of effecting the sacas and rocíos in a solera is called correr escalas (running the scales).

These movements of wine within the solera are known as trasiegos, and the bodega workers who specialise in the tasks involved are called trasegadores. They have to work with extreme care using special equipment and painstaking, traditional methods. Their skill resides in being able to homogenise all the wine contained in a butt after the rocío without disturbing the film of flor covering the surface of the biologically ageing wine or churning up the cabezuelas, or fine lees, that accumulate gradually at the bottom of the butt over the years.

How often these operations take place and what proportion of wine is extracted are rigidly dictated by the wine's characteristics, since these factors influence the duration of the ageing process. The average ageing period in the solera system assigned to a wine is calculated by dividing the total volume of wine contained in the system by the volume of wine extracted from the solera annually. In accordance with the norms established by the Consejo Regulador, and with the aim of not putting sherry wines onto the market with less than two years of ageing, the said proportion must be greater than two.

The solera system imprints a very special dynamic on the ageing process, and influences the nature of the wine in a singular way. It maintains the characteristics of the wine in the solera while eliminating the variations that occur between one vintage and another.

Furthermore, the solera system provides significant benefits for biological ageing under velo de flor since, during this type of ageing, wines are subjected to continuous, intense metabolic action from the film-forming yeast. Maintaining this culture requires essential micro-nutrients, and these are provided by adding small quantities of wines from young añadas; in the course of successive 'refreshments', small quantities of young wines reach the oldest scales. This tops up the contents with the compounds necessary to support vigorous biological ageing under a film of flor yeast which might decline but for this nutritional input.

The continuous transferral of wines within the solera system also has the effect of dissolving a certain amount of oxygen in it, thereby stimulating regeneration and growth in the film of flor which will have deteriorated slightly in the process. This input of oxygen is rapidly consumed by the yeasts' breathing, however, and the wine remains protected beneath the inert atmosphere that the velo de flor provides for it. In solera wines aged non-biologically, or simply aged, the oxygen introduced during decanting operations accelerates the oxidative processes of wine maturation.

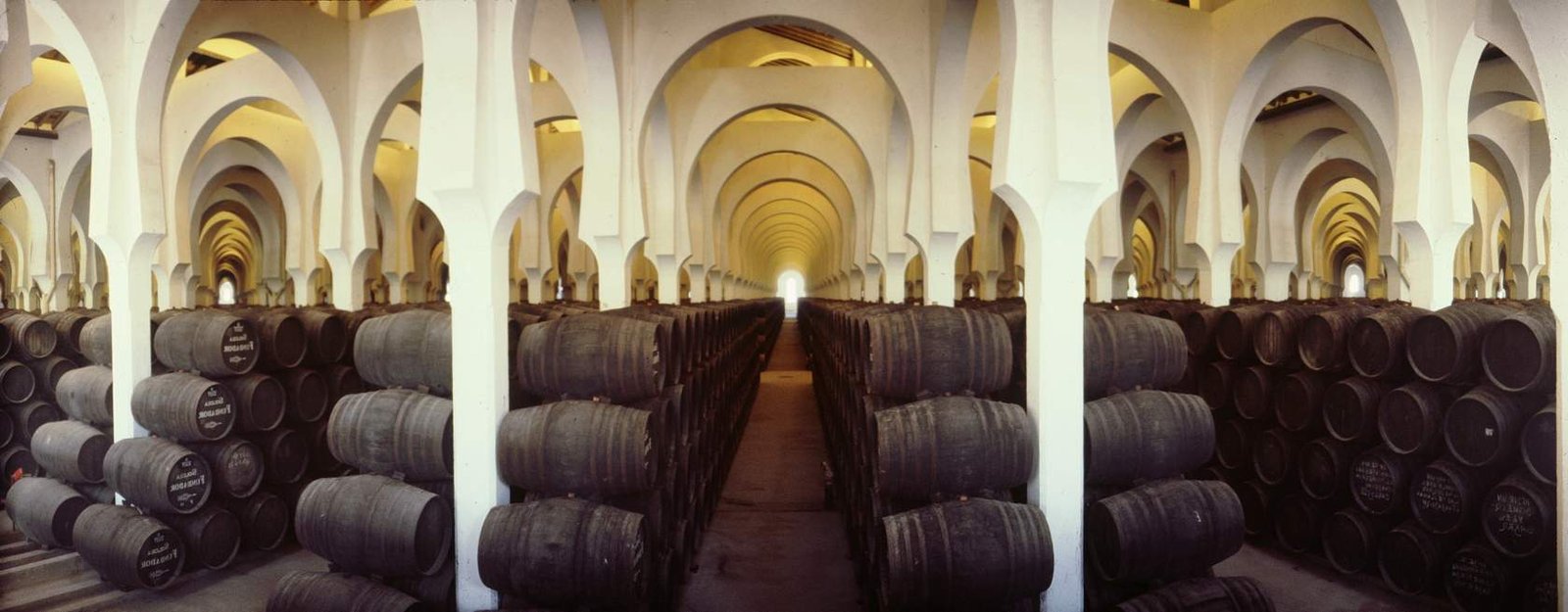

The complex processes which make possible the ageing and maturing of sherry wines require the existence of very precise environmental conditions, ones that are not always available given the climate of the Jerez Region. Warm and southern in nature, but with the strong influence of the Atlantic Ocean, the climate of the region produces strong oscillations in temperature, changes in levels of humidity according to the dominant winds, etc... This has forced the sherry firms in the Jerez Region to adapt the architectural design of their bodegas in order to diminish the negative factors of the climate and take advantage of the more positive aspects.

If we take a look at the sherry bodegas in the Jerez Region we may conclude at a first sight, from an aesthetic point of view, that they are very beautiful buildings and are frequently an impressive sight due to their dimensions. But if in addition we analyse them according to the requirements of the sherry ageing systems we discover that they are also extremely functional in their design.

In a bodega, both the orientation of the ground plan and the structural characteristics of the façade and roof behave as filters that slough off those elements of the weather that are harmful to the ageing wine and allow in the beneficial ones. Fluctuations in temperature inside the building are prevented by the walls' thermal inertia and permeability to moisture, so that day and night hygrothermal conditions are kept constant. Bodegas are built in strategic places where the gentle southerly and westerly winds blowing in from the Atlantic can circulate easily. These breezes are laden with the moisture needed for the development of flor.

The rectangular shape of the bodega floor-plan adapts to a northeast-southeast axis so that moisture can get into the interior of the bodega unimpeded, yet blocking the harmful, strong, dry levante winds blowing in from the east and north-east. The way that the winery is oriented also minimises the effects on its walls of the hours of strongest sunshine.

Bodegas in Jerez are unusually tall buildings, sometimes as tall as 15 metres at their central arch. The interior space of a bodega consists of a large volume of air whose function it is to provide flor yeast with the oxygen it needs to develop inside a butt. Additionally, this huge space acts as an insulating chamber that regulates temperature and humidity. Its height is conducive to induced ventilation - a stack effect caused by the difference in temperature when the wind is not blowing from the Atlantic. The heat tends to rise and accumulate in the bodega's upper spaces; by means of vents placed high up in the east and west walls, a dynamic vertical and horizontal draught is created that pushes the accumulated hot air out.

In summer, the south façade of a bodega is shielded from the sun by screens of vegetation in the form of trees or pergolas in the streets that run alongside it. These serve as natural sunshades, absorbing the sun's radiation and providing perforated canopies that let through the gentle breezes that make their way into the winery and keep hygrometric conditions at the proper levels. In winter, when the leaves of these deciduous canopies fall and leave the walls exposed, the big expanses of whitewashed façade attract the sun's rays, storing the heat and transmitting it to the bodega's interior during the night.

The windows are generally set high in the upper third of the walls. They are small, rectangular or square in shape, and arranged in symmetrical, repeated rhythms. The arches that support the roof structure are designed to let the breezes in and allow the air that comes in perpendicular to the nave's longitudinal axis to circulate. The height at which the windows are placed, and the esparto-grass blinds with which they are covered during the day, create a diffuse, diagonal light that remains consistent despite the changing position of the sun in relation to the walls of the building. In addition to controlling the quality of light, the blinds and lattices sometimes placed in the vent openings filter the air, preventing dust or undesirable insects from getting in.

The uniformly subdued light inside the bodega also serves as a temperature regulating instrument, and is essential to preventing any disturbance in the butts. Bodega walls are usually single-skin and at least 60 centimetres thick, so that the wall mass, which is thermally very inert, compensates for the absence of any specific thermal insulation. The walls are built of very porous material which also contributes to producing high levels of humidity. The bodega floor is covered with albero earth which, according to the season, can be sprinkled with water to regulate the temperature and humidity inside the building. Albero is a very porous material that, when saturated, lowers the temperature and keeps it cool by gradually releasing water into the atmosphere.

In short, a whole range of building techniques which provide the wine with the ideal habitat in which ageing process is allowed to develop under optimal conditions.