We refer to a barrel as a cylindrical container, generally longer than it is wide with convex walls formed by wooden battens and closed at the two ends by round flat wooden lids. The longitudinal pieces which form the cylinder – known as staves – are fitted tightly together using hoops, almost always made of metal.

Since remote times the wooden barrel has been the ideal container both for the storage and transportation of wine since its cylindrical shape makes it easy to move. The first representations of wooden barrels of which we have constancy date back to the 1st century AD and can be seen in a curious Roman bas-relief conserved in the Brotte Wine Museum in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, France. It consists of a stele found in the municipality of Cabrières d'Aigues in which can be seen a barge for river transport loaded with what look like wooden barrels. However it does not seem that the barrel was a Roman invention, but that they adopted it from its original creators, the Gauls, improving on their more rustic model by incorporating metal hoops.

It is interesting that this first Roman representation shows the barrels on the deck of a ship as throughout history we find continuous parallels between cooperage and the world of navigation. Not only do the fabrication methods have much in common, like the use of wooden battens and metal hoops, but also since remote times the alliance between the boat and the barrel has allowed the development of transporting goods round the world. It is interesting to note that in Spanish a general term for a barrel is “tonel” giving the word “tonelada”, or the weight of a full barrel (1 ton). It is the same in English where the origin of the word “ton” is “tun” a wooden wine vessel. Until the invention of the metric-decimal system, a tonelada referred to the space needed for a tonel of liquid in a ship, and “tonelaje” to its cargo capacity.

There are occasions when the word “tonel” does have specific measurements and capacity, while in general the term “tonelero” (cooper) is applied to the professionals who make all sizes of wooden containers of that shape, including open containers called “cubas”(vats).

Cooperage in Jerez has become a unique world of its own: from the peculiar tools used in the processes of fabrication and repair, many of them are of a pure artisan nature, to their own vocabulary in which each task, each tool, and each piece if the barrel has a name of its own. In the corresponding section of this chapter, we have included a glossary of terms specific to cooperage in Jerez.

The Sherry cask story begins in the oak forests located both in Europe and America; in forests in the North of Spain or in regions as distant as Missouri, Pennsylvania or Kentucky. The American white oak of the species Quercus Alba is preferred for the ageing of Sherry although frequently Sherry casks are also made with wood from Spanish oak (Quercus Pyrenaica) or even French oak. As with any other cultivation, forestry or management of the oak forests requires very careful methods which ensure both sustainability and the obtention of a high-quality product.

We are talking about trees which are felled at an age of between 120 and 160 years, so the entire process from planting the seedlings, thinning the forest and the never ending care up to felling require extremely long term planning.

Trees selected for felling will have a height of 30-40 metres and a girth of 40 cm. The wood suitable for the cooperages amounts to about 40% of the trunk and is always taken from the central part (duramen or heartwood) of the lower trunk. The rest of the wood will be used for cabinetmaking, carpentry, flooring etc.

With the subtle differences between each species of Quercus, oak has prevailed as the world’s favourite wood for the fabrication of barrels and containers for liquids – especially wines – not only because it is watertight but also for its capacity of micro-oxygenation of the liquids stored in it and the very interesting elements it leaches into the wines or spirits during ageing.

The first stage in the long process of making a Sherry cask is the longitudinal cutting of the wooden planks which will later become the staves of the butt. The saw line must run along the natural grain of the wood to guarantee waterproofing.

Once the rough shape of the staves has been cut they need to be dried in the open air. They are stacked in such a way that there is space between them to allow the passage of air. During approximately two years of weathering, the rain, the sun, and the air reduce the greenness and bitterness of the wood, softening its aroma and reducing its water content to between 12% and 15%. Every so often it will be necessary to change the position of the staves to ensure even drying.

Once the natural drying period has elapsed and the exact moisture has been checked the great piles of staves are dismantled for the exact shaping of the pieces which will form the butt and give them the perfect shape for assembly. Before starting, each stave is closely examined and any with flaws after drying are discarded. Using specialised machinery the “dolador” or stave specialist prepares the wood by cutting and planing it to give it the characteristic shape of a stave with the ends narrower than the middle.

Raising a cask requires great skill: firstly the staves have to be roughly assembled into a hoop “aro de mole” (raising hoop) forming a slightly conical open structure into which the upper ends of all the staves are fitted, between 32 and 36 depending on the diameter of the butt. Once this initial framework has been formed, the staves are compressed tightly into position with the addition of more hoops which are hammered downwards into place until the upper part of the structure is completely rigid.

The next stage is to bend the lower part of the structure in order to bring together the other ends of the staves. This is accomplished using a combination of two elements: fire and water. In the “batidero” (a covered area with a patio) the nascent butt is placed over the mouth of an underfloor oven (cresset) fuelled by oak leftovers like shavings and chippings and the heat from this helps to soften the wood. Pressure is then applied using a steel loop “aro recogedor” (truss hoop) which tightens round the lower part of the structure while water is applied to the wood to give it a certain degree of flexibility and stop it burning. At the end of this process the lower ends of the staves have been drawn together and the cask is the same at both ends. At this point all the hoops are hammered into place and the cask is ready for finishing.

Obviously finishing is the final phase in the manufacture of a cask during which the coopers work on machining its extreme ends (tiestas). The first job is called “descapirota” in which the tips if the staves are smoothed off to equal length and a groove (jable) is cut round the inside at each end to locate the heads of the cask which have been made separately. Then the inner edges of the stave ends are bevelled (fleteado) at a suitable angle for the thickness of the stave (explayado). All these operations are known collectively as “arrumado”.

The heads of the casks each consisting of seven or more pieces – each one with its own name – are made separately. After the heads have been fitted the cask is ready for the final steps: sanding the exterior, positioning of the final metal hoops and drilling the bunghole (boca de bojo), a circular hole in the widest part of the cask. Now all that remains to be done is to check that it is waterproof.

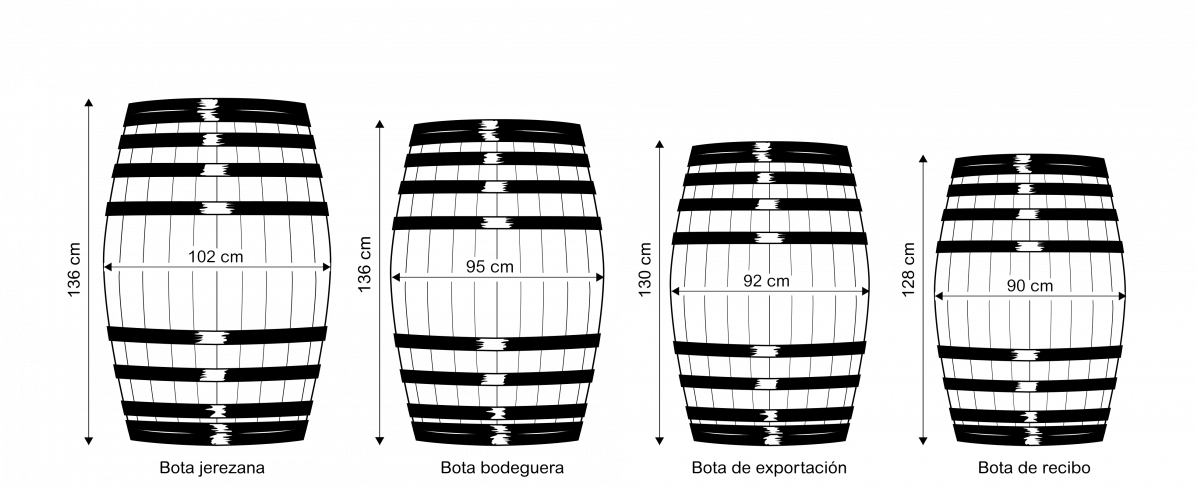

In Jerez the ageing vessel par excellence is the “bota jerezana” with a capacity of 600 litres (equivalent to 36 arrobas). Although its dimensions can vary slightly depending on the cooper, they are usually approximately as follows: 136 cm long (la talla), 102 cm at the widest point (el bojo). The vast majority of the wines protected by the Denomination of Origin age in this type of container although often they are only filled to 5/6 of their capacity to propitiate the development of the veil of yeasts which we call “la flor”, a vital element for “biological ageing”. This type of cask is also commonly known as a “bota gorda” (fat cask). The “bota de exportación” or export butt, the one used in the past for transporting the wine, has a capacity of 500 litres (30 arrobas) and dimensions of 130 cm long, by 92 cm wide.

The “bota de recibo” (receipt cask) was traditionally used for adjustment in the buying and selling of wine and has a capacity of 516 litres (31 arrobas) and dimensions of 128 cm long and 90cm wide. Finally, there is the so called “bota bodeguera”, often used in the lower scale of the solera system for its larger capacity and strength or for various internal tasks in the bodega. It has the following average dimensions: a capacity of 566 litres (34 arrobas), length of 135 cm and width of 95 cm. Apart from those vessels already mentioned there are others which have been or continue to be used like the “media bota” (half cask) of 250 litres with dimensions of 100 cm long by 72 cm wide, the 700 litre “bocoy”, the “cuarta de bota” (quarter cask) of 125 litres and the “octavo” (octave) of 62.5 litres.

The lifespan of the casks used for ageing Sherry is almost unlimited. In fact the older a cask is – assuming it is in good condition – the more valuable it is; something totally different to what happens in most wine regions. The lifespan of a cask depends on many factors however: the conditions in the bodega, its location in that bodega, the weight it is supporting and even the wine it contains. And of course how carefully it is treated.

Coopers also play a fundamental role in the bodega as they are responsible for looking after all the barrels and repairing any which may occasionally develop faults. All bodegas over a certain size have their own cooperage department, while smaller bodegas will rely on external cooperages for the maintenance of their casks and any repairs.

It is by no means uncommon, when wandering through the darkness of an ageing bodega, to meet a cooper who, with a torch in one hand and chalk in the other, is busy marking those casks which need some sort of repair. Sometimes it is small leaks which shine out against the matt black with which all the casks in the bodega are painted. Other times it might be heading off potential problems, identifying some anomaly in the rows of casks, like bulging casks, defective hoops or curving heads which could lead to future breakages.

Once the casks which need attention have been marked, the capataz (cellar master) needs to make plans for their removal in a way which will disrupt the running of the criaderas and solera to the minimum possible. The degree of urgency of the repairs will decide in great measure the order of the plans. The wines contained in the casks needing repair will be transferred temporarily to tanks or spare clean casks and once the original cask is empty it can be removed from its row and taken to the cooperage

Occasionally, if it is a “bota condenada” (one which supports the weight of others) it will require what is known as a “puente” (bridge). This laborious task consists of distributing the weight of the casks above the one to be removed to adjacent ones taking any weight off it. The “arrumbadores” (bodega workers expert in this kind of job) use various types of wooden wedge which they skilfully distribute among the other casks gradually spreading the weight and releasing the cask to be repaired.

Once at the cooperage the cask will be dismantled, freeing the staves from the hoops and heads. Any faulty components will be discarded and the others will be carefully inspected and classified as to their age, condition, and type of wine they have contained. In the patios of the repair workshops, hundreds of staves, hoops, and heads have been accumulated ready to use as spare parts for rebuilding the butts back to perfect condition.

While the “tonelerías de nuevo” (cooperages which make the casks) have been incorporating specialised machinery for some of the steps in the process, the so-called “tonelerías de viejo” (repair cooperages) do practically everything the artisan way.